The governments which have signed the UN Framework Convention of Climate Change (UNFCCC) meet annually to discuss how to jointly address climate change at a Conference of the Parties (COP).

The COP21 in Paris in 2015 concluded an international treaty, the “Paris Agreement”, which aims to keep the rise in the global average temperature to “well below’” 2°C above pre-industrial levels, ideally 1.5°C.

The “Paris Agreement” means countries themselves decide how much they will reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by a certain year. They communicate these targets to the UNFCCC as a nationally determined contribution (NDC) every five years. The NDCs pledges submitted in 2015 collectively meant that the world was on a trajectory well above the 2°C target.

Rapid international collaboration is required to get the world back on track to reduce carbon emissions. It is often said that to have a chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C, global emissions must halve by 2030 and reach ‘net-zero’ by 2050.

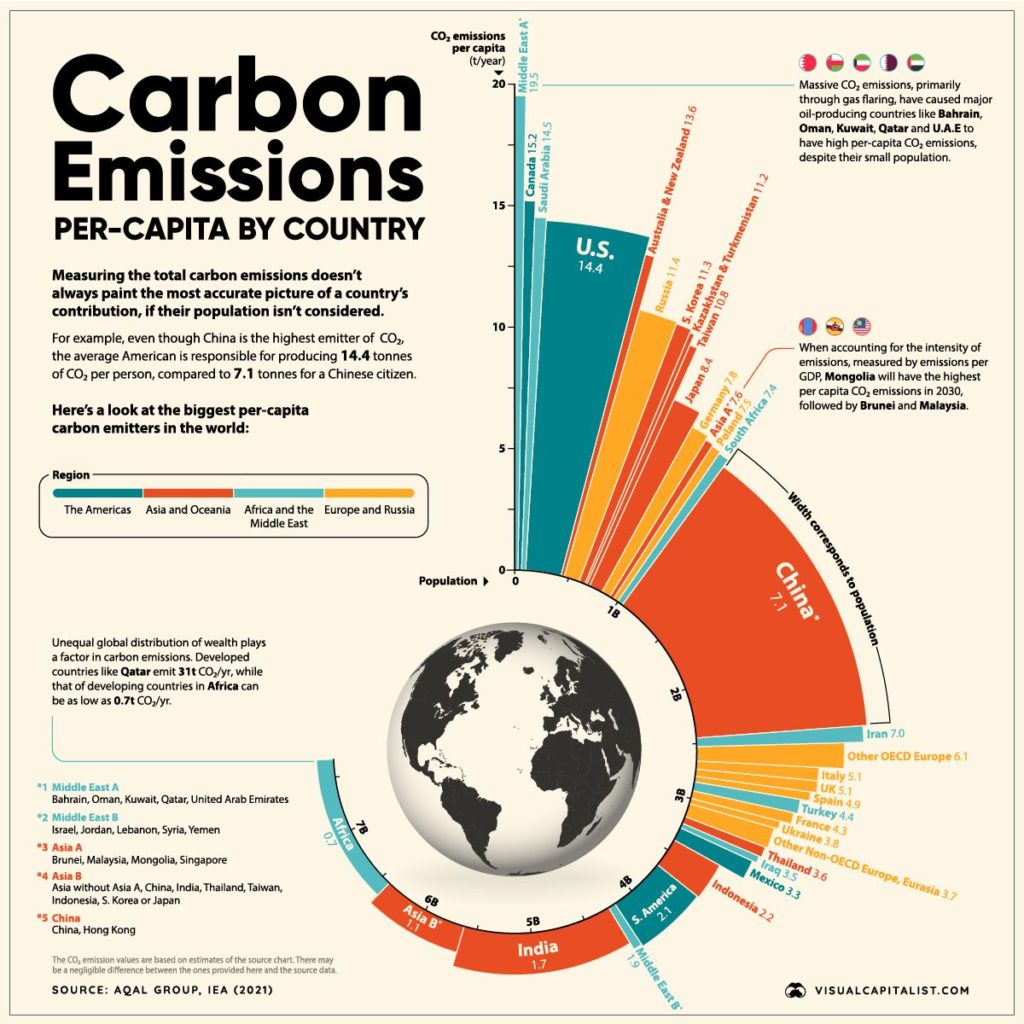

One chart which reveals the magnitude of the task is “Global Carbon Emissions per Capita by Country” authored by VisualCapitalist using International Energy Agency 2021 data. A per capita perspective shows both the changes required from the world’s 7.9 billion population and illustrates the cooperation required between countries.

The COP26 in Glasgow in 2021 was the first time the signatories of the Paris Agreement were required to submit new, more ambitious, NDCs. The 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change, made it very clear that unprecedented action was required now.

One of the most important new announcements at COP26 was India’s pledge to reach net zero emissions by 2070.

The outcome of COP26, the “Glasgow Climate Pact” resolved to limit global warming to 1.5°C, instead of the weaker Paris text of “well below 2°C”, but the new NDCs submitted were not aligned with this target – they aggregated to a global average temperature rise of 2.4°C in 2100 at best. A resolution asking the signatory countries to the “Paris Agreement” to further renew NDCs by end 2022, and, specifically, to revisit and strengthen their 2030 goals, was included.

Non-binding pledges to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030, end deforestation by 2030 and the phase out coal were also made at COP26 in Glasgow. It was widely reported that the “Glasgow Climate Pact” text on coal was watered down, with the phrase “phasing out” replaced with “phasing down”, but the first mention of this issue in a COP is positive news.

The finalisation of guidelines – the “Paris Rulebook” – for the full implementation of the “Paris Agreement” was achieved at COP26. This included “Article Six” relating to carbon markets. “Article Six” aims at promoting greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction through voluntary international cooperation. Under this mechanism, countries with low emissions could sell their allowance to countries with high emissions, within an overall cap of global GHG emissions, ensuring a net GHG emission reduction. “Article Six” could establish a policy foundation for an emissions trading system, which could help lead to a global price on carbon.

But perhaps the most important progress was on the side lines of COP26 in Glasgow. The “U.S.-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s” establishes a bilateral working group to cooperate on reducing methane and carbon dioxide emissions in each country, the world’s two largest carbon emitters.